Introduction to Soil

By Jake Eiting, Horticulturist

In horticulture and gardening, soil care is one of the most important factors in maintaining a healthy and vibrant garden. When we walk into a beautiful garden and admire the colors, textures, and fragrances, we’re viewing but a part of the living whole. While your attention is usually focused on the aboveground aspects of light, watering regimen, and temperature, attention must also be paid to the world below ground.

A significant portion of any plant, its root system, lives in the soil. At a very basic level, roots uptake nutrients and water, which are then transported through the xylem, or water-conducting tissue, to the shoots and leaves for use in metabolic processes including photosynthesis.

The underground life of a plant is dynamic with a multitude of interactions and processes. Soil fauna, fungi, bacteria, and other beneficial microorganisms thrive in the rhizosphere, a vast yet narrow zone of soil immediately adjacent to a plant’s roots. As plant roots grow in density, length, and diameter, they push through the soil in search of water, and the rhizosphere keeps expanding. The roots also secrete exudates that lubricate the adjacent soil, feed beneficial fungi, suppress pathogens, and compete with neighboring plants.

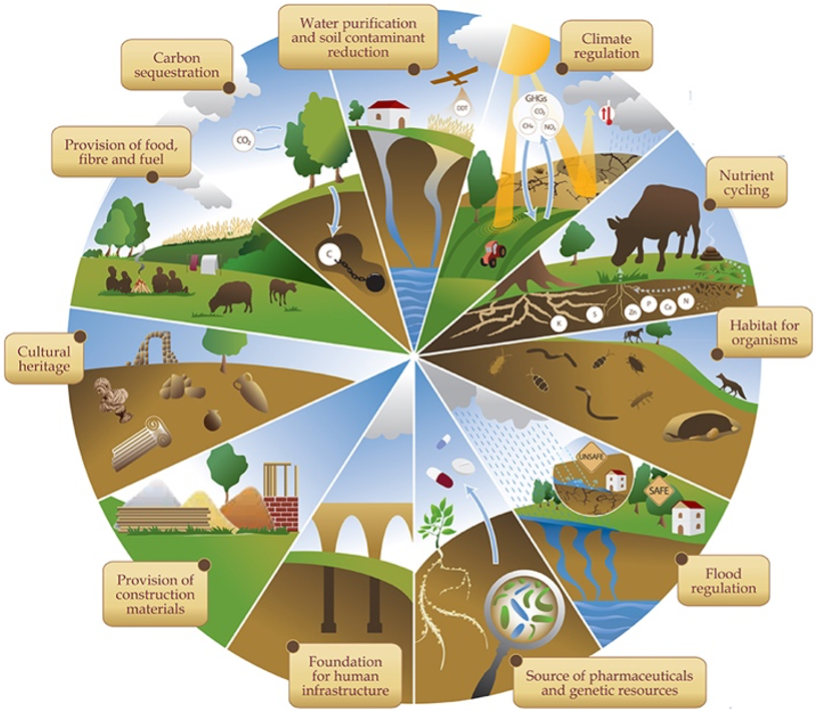

Soil is a foundation for plant life on our planet, and in turn the plants of the world support the upper tiers of the trophic pyramid. Humans rely on soil for every meal we eat, whether directly or indirectly. Beyond food, soil provides numerous environmental services such as filtering groundwater, recycling wastes, sequestering carbon, and providing habitat for a diverse community of microorganisms such as nitrogen-fixing organisms, plant-beneficial bacteria, and fungi. Understanding the interconnectedness of the world of soil within the global ecology helps us to realize not only the myriad connections throughout our natural world, but also to realize how undeniably connected humankind is to nature.

Image 1: The main ecosystem services provided by soils. Credit: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Soil Formation

Look across the globe and you’ll find that soils differ greatly from one another. The number of soil types are as numerous as the services that soils provide for life on Earth.

The components of soil formation are summarized by the acronym CLORPT, which stands for climate, organisms, relief (topography), parent material, and time. Each element changes the innate characteristics of a soil. For example, a soil born of mountainous terrain, with a granite parent material that receives frequent precipitation and supports large forests, will look and act significantly different than a soil born of a relatively dry desert with a sandstone parent material that receives very little annual precipitation and supports less biomass.

Likewise, the timescales on which soils develop vary greatly and can be an extremely lengthy process. In the continental United States, soil is created, on average, at a rate of about .36mm per decade. That is to say that 254mm, or 1 inch, of soil takes about 700 years to form. These numbers highlight the need for conscientious soil stewardship and are perhaps most striking when remembering our lives are directly connected to the soil.

Image 2: Adapted from © FAO 2015 ‘How soil is formed’ www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/284480

Utah Soils

Utah is home to a wide variety of soil types from the heavily salt-influenced soils of the West Desert to the high alpine soils of the Uinta Mountains. This map provides a glimpse at Utah’s diverse soil palette. Soils along the Wasatch Front and throughout central Utah are generally well-developed grassland soils that usually exhibit a dark, organically rich topsoil and are easily cultivated for vegetable production or growing healthy ornamental plants, while some areas have sandy soils, which benefit from the addition of organic matter. There is, of course, variation in soil from place to place and the management history of a plot of land will influence soil qualities. If you don’t know the history of your soil, or are curious about learning more, consider having your soil tested.

Fungi and Fauna

Soil is incredibly dense in biodiversity. Just one teaspoon of fertile soil contains about one billion bacteria, meters of fungal hyphae, and many miscellaneous microorganisms or soil fauna. Soil fauna includes earthworms, insects, arthropods, and a host of microorganisms such as bacteria, algae, protozoa, and nematodes. Some churn the soil, improving its structure, while others assist in the decomposition of organic matter, releasing nutrients so they’re available for use. While much of the soil fauna have roles that benefit the soil community and plant life, others include parasites and diseases, while still others are predators (of other soil fauna) or regulate disease.

Of all the organisms living within the soil, fungi forms direct relationships with plants and aids them in obtaining key nutrients required for everyday function. Mycorrhizae translates to ‘fungal root’ and refers to the symbiotic relation between plant roots and Mycorrhizal fungi. This beneficial connection essentially expands the plant’s root system to include the large hyphal network (hence ‘fungal root’), vastly increasing the overall surface area of a plant’s root system for nutrient and water uptake. In exchange the fungi receive carbohydrates, which it is incapable of making itself.

Most land plants will form relationships with mycorrhizal fungi, however some plants do not. Members of the Brassicaceae family (broccoli, cauliflower, kale, cabbage) and some members of the Amaranthaceae family (spinach) do not associate with mycorrhizal fungi.

Ultimately the vast complex web of soil life enhances the entire ecosystem and ensures conditions necessary for plants to thrive.

For more information, see our articles on Soil Science Fundamentals and Managing Your Soil.